The Hadoop Ecosystem

What I Learned: (Some of) How the Hadoop Ecosystem Fits Together

This week’s project was to get a better understanding of how many of the Hadoop-related products and services fit together, and what their basic functions are. So, I took a course on Udemy and did a bit more reading (note: images in this blog are from the Udemy course). While there were many practical examples I worked through in the class, my goal at this point is not to become an expert in any one technology, but rather to get a solid conceptual feel from which to build in the future. Spark and working with streaming data are two areas in particular that I will definitely look into more!

What is Hadoop?

The basic summary is: “Apache Hadoop is a collection of open-source software utilities that facilitate using a network of many computers to solve problems involving massive amounts of data and computation.”

Essentially, Hadoop provides a software framework to handle the storage and processing of Big Data. It solves the problem of having too much data to store in a traditional manner by using a cluster of computers in one single file system. It can be scaled horizontally by adding more machines, vs. vertically by adding more power to an existing machine (which can be challenging or reach limits), and has redundancies in case of failure. Hadoop also allows for the storage of semi- and unstructured data sources (like text, videos, etc.). Processes can be completed on these data in parallel, allowing for much faster analyses.

Hadoop consists of four main modules:

- Hadoop Distributed File System (HDFS) for distributed storage

- Yet Another Resource Negotiator (YARN) to manage and monitor the cluster nodes.

- MapReduce for parallel computation.

- Hadoop Common, libraries and services that support other Hadoop modules.

There are tons of tools and applications that are part of the Hadoop ecosystem that also help with the collection, storage, processing and analysis of Big Data.

HDFS

The Hadoop Distributed File System (HDFS) is the primary data storage system used by Hadoop applications. It allows for the storage of very big files by breaking them up into “blocks” which can be stored across one or more machines in a cluster. This also makes parallel processing quite efficient.

Copies of the blocks are stored as a security feature. Because of this redundancy, Hadoop is able to make use of less expensive commodity hardware.

HDFS uses a master/slave architecture, where each cluster consists of a single NameNode that manages the file system operations (like keeping tracking of where the data blocks live, and maintaining edit logs of what is created, modified, or stored), and several supporting DataNodes. The DataNodes manage the data stored on the individual compute nodes, and are what the client application talks to when it queries the NameNode for some piece of information. The DataNodes also communicate between each other.

While only one NameNode can be active at a given time, it is possible for there to be a backup node that also has access to an edit log in case the first node has a failure. Alternatively, HDFS Federation allows for NameNodes per subdirectory, which is important if storing many smaller files (since HDFS is really optimized for fewer larger files). A final option is HDFS High Availability, which constantly maintains a hot standby NameNode with a shared edit log to avoid any downtime if the first NameNode goes down.

HDFS can be accessed through a UI like Ambari or Hue, the CLI, HTTP (directly or through proxy servers), network file system (NFS) gateway, or through a Java interface.

YARN

Where HDFS manages storage resources across a cluster, Yet Another Resource Negotiator (YARN) manages the computational resources. YARN can execute specific jobs or tasks that depend on data in HDFS, and determines where applications are processed. It aims to optimize the usage of a cluster from both CPU and data locality standpoints. There are also several scheduling options for jobs.

Many applications in the Hadoop ecosystem are written on top of YARN (like MapReduce, Spark, and Tez).

It is also possible to use other resource negotiator tools instead of YARN altogether. For example, Mesos is an option that is not restricted to Hadoop and is more general in scope: it manages computing resources across an entire data center, and not just Hadoop applications.

MapReduce

MapReduce allows for the distributed processing of data on a cluster. It facilitates concurrent processing by splitting large amounts of data into smaller chunks, and processing them in parallel on the Hadoop servers. In the end, it aggregates all the data from multiple servers to return a consolidated output back to the application. With MapReduce, rather than sending data to where the application or logic resides, the logic is executed on the server where the data already resides to expedite processing

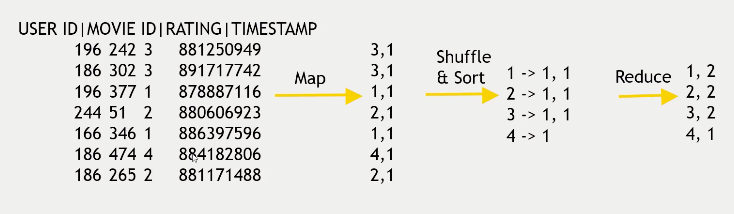

To do this, a mapper first converts data into key:value pairs. For example, say we are interested in how many movies a particular user on a website has rated. If the user id was 2, and they rated movie id 34, the key value pair would be 2:34. MapReduce then sorts and groups values using “shuffle and sort,” which means that it looks at individual key value pairs and maps all the values for each unique key, resulting in one key and a list of all related values. So, if user 2 rated four movies with movie ids 34, 56, 708, and 25, the final result would be: 2: 34, 56, 708, 25.

Given the output from shuffle and sort, the reducer step aggregates the data. In the example of looking for the number of movies rated per user, the reducer would look at the length of the values in each key value pairing. For user 2 who rated four movies, the output from the reducer would be 2:4.

These processes may take place across multiple computers or processors: it is possible to split up the mapping and re-sort using a merge sort during the shuffle and sort process, and multiple reducers may take responsibility for different sets of keys. This coordination is handled through YARN.

MapReduce problems can be written in MapReduce directly, with SQL, or by using streaming to write in a language like Python.

Another example: Count how many of each star ratings (1 through 4) exist in a dataset:

In this case, the key is the rating, and the value is always 1 during the mapping step, as it just counts an instance of a particular rating. Shuffle and sort will end up with a list of 1s the length of the number of discrete reviews. The reduce step calculates the list’s length to determine the number of reviews per rating.

It is, of course, possible to complete multiple map and reduce steps. The output of the first reducer is sent to the next mapper as input, or reduced again directly.

Another option for MapReduce-like processes is Tez. Tez is much faster because of its use of DAGs to optimize data flow, which allows for more efficient processing of distributed jobs and fewer unnecessary steps. With MapReduce there is a fixed chain of events from mapper > reducer, but Tez can look for interdependencies and try to determine an optimal path. Clients like Hive and Pig can use Tez as a replacement for MapReduce, and Tez can even be used to speed up MapReduce jobs themselves.

Some External Modules

Zookeeper

Zookeeper keeps track of track of information that needs to be synced across a cluster, like which node is the master, which tasks are assigned to which workers, which workers are available, etc. It is an external tool that applications in the Hadoop ecosystem can use to recover from partial failures in a cluster.

Oozie

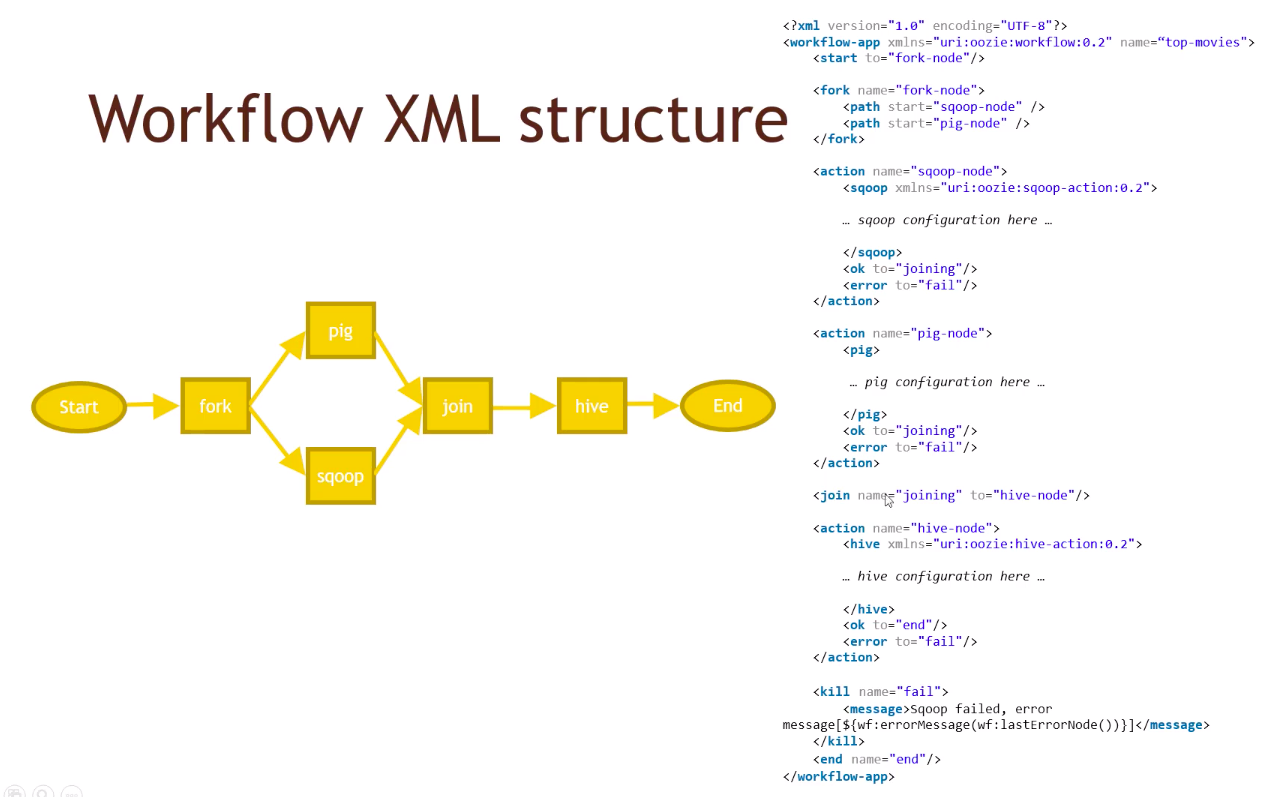

Oozie orchestrates Hadoop jobs. Different Hadoop processes that depend on each other are tied together into one workflow using a DAG, specified through an XML file. Like so:

Pig

Pig (short for Pig Latin) is a scripting language that is built on top of MapReduce (or Tez) to allow for the creation of MapReduce jobs without needing to write mappers and reducers directly. It is like SQL, but procedural (step-by-step, with reassignment at each step), and is highly extensible with custom user defined functions.

A simple Pig script might look like the following. This script finds the oldest movie in a dataset with a five-star rating.

-- load the ratings data and define schema

-- anything not part of the explicit schema just doesn’t get loaded in.

ratings = LOAD ‘data/ratings.data AS (userID:int, movieID:int, rating:int, ratingtime:int);

-- load the metadata (file has a pipe delim) and define schema

metadata = LOAD ‘data/metadata.data’ USING PigStorage(‘|’)

AS (movieID:int, movieTitle:chararray, releaseDate:chararray);

-- convert metadata into new relation with a timestamp

-- for each row in metadata, generate a row with the columns from the first and the new col.

nameLookup = FOREACH metadata GENERATE movieID, movieTitle,

ToUnixTime(ToDate(releaseDate, ‘dd-MMM-yyyy’)) AS releaseTime;

-- gather all ratings into a tuple by movieID

ratingsByMovie = GROUP ratings BY movieID;

-- go through the ratingsByMovie relation and generate an avg. rating per movie from the rating relation rating field

avgRating = FOREACH ratingByMovie GENERATE group AS movieID,

AVG(ratings.rating) AS avgRating;

-- filter for only movies with an average rating above 4

fiveStarMovies = FILTER avgRatings BY avgRating > 4.0;

-- join the fiveStarMovies and nameLookup by movieID to get the names and dates of 5 star movies

-- JOIN returns table names like table::column

fiveStarsWithData = JOIN fiveStarMovies BY movieID, nameLookup BY movieID;

-- order the joined data by the nameLookup table releaseTime column.

oldestFiveStarMovies = ORDER fiveStarsWithData BY nameLookup::releaseTime;

-- run command and display head

DUMP oldestFiveStarMovies;

Hive

Hive is like Pig, but even more SQL-like. It uses HiveQL, which is basically just MySQL syntax, and translates this to MapReduce or Tez. It is quite intuitive, but may not be able to handle super complicated procedures as well as Pig or Spark. Hive is also higher-latency, so isn’t a good fit for online transaction processing (OLTP).

Hive takes unstructured data and applies a schema to it as it’s being read (called “schema on read”), which differs from normal databases that are “schema on write.” In this case, just text files actually being stored, not separate tables that are normalized with keys, for example. Because of this, no transactions or record-level inserts or deletes are possible.

Side note: normalized data are organized and eliminate redundancies. They are slower than denormalized databases where the same date may be all over the place.

HBase

In cases where many fast, simple transactions are needed, relational databases may be too slow (for example, movie recommendations for a customer on the page at this moment). NoSQL is an alternative that can answer questions quickly and can scale horizontally forever.

HBase is built on top of HDFS, and allows for NoSQL-like access. This is useful for simple use cases and high transaction rates that need to access data on the Hadoop cluster. It does not have a query language, just uses an API for CRUD operations. The idea is transactional access vs. analysis.

HBase is separated into database regions, each of which is responsible for a different range of keys (basically auto-sharding, or separating the rows of a table into different tables/partitions). There are master servers that keep track of where everything is, and the data itself is stored in HDFS.

Each row is referenced by a unique key, and has some small number of “column families.” Each column family can contain a large number of individual columns, which is useful for sparse data. Each cell (intersection of a row and column) can have many versions with stored history and timestamps.

Cassandra

Cassandra is another NoSQL distributed database option. It does have a limited query language called CQL, but since the database is not relational it is still not optimized for this like joins. Rather, Cassandra is specifically engineered for high availability in environments where there are lots of transactions that need fast access.

Cassandra achieves high availability through the “gossip protocol”: every node communicates with all the others all the time. All nodes run the same software, are doing the same thing, and essentially manage themselves without a master node. As a trade-off, Cassandra is less “consistent”: nodes may send different answers. This can be handled by requiring that the same answer be received from multiple nodes before it is accepted.

MongoDB

MongoDB is one more NoSQL database. It can handle structured or unstructured data - basically whatever can be put into JSON format, and can use a schema, but doesn’t have to. It has a single master node to ensure consistency, which can lead to a lack of availability if it goes down.

MongoDB has built-in aggregation capabilities, can run MapReduce, and has its own file system like HDFS called GridFS. It has its own SQL connector, so can be queries using normal SQL, though it is still not really a relational database, so isn’t the best for working with normalized data. MongoDB is on the more corporate side of things, so is more expensive and has better support options.

Choosing a Database

CAP Theorem

The CAP theorem says that in a distributed database system, one can only have two out of consistency, availability, and partition tolerance. Quotes for the descriptions of each come from this article.

- Consistency: “All nodes see the same data at the same time. Simply put, performing a read operation will return the value of the most recent write operation causing all nodes to return the same data.”

- Availability: “This condition states that every request gets a response on success/failure. Achieving availability in a distributed system requires that the system remains operational 100% of the time. Every client gets a response, regardless of the state of any individual node in the system.”

- Partition tolerance: “A system that is partition-tolerant can sustain any amount of network failure that doesn’t result in a failure of the entire network. Data records are sufficiently replicated across combinations of nodes and networks to keep the system up through intermittent outages.”

Something like MySQL would have high availability and consistency. Since partitioning is necessary for distributed systems, this implies a tradeoff between consistency and availability. Cassandra tends to prioritize availability, while MongoDb and HBase prioritize consistency. That being said, there have been many technical advances which mean CAP isn’t a hard and fast rule, more just something to consider.

Other Considerations

- What systems need to be integrated together?

- Scaling requirements - will the data grow unbounded over time, or not?

- Transaction rates

- Support consideration

- Security

- Price

- Simplicity

Streaming Data: Kafka and Flume

Streaming data publishes data from data sources into the cluster on an on-going basis. This could be log data, sensor data, or stock trade data, for example. It may be stored, or processed right away.

Kafka and Flume are two options for this.

Kafka is not just for Hadoop. It is comprised of a cluster of servers which store incoming information from publishers, and then publishes this data to consumers. Specific streams of data are called topics, and consumers subscribe to one or more topics to receive the data as it’s published. Data can be published in real-time, but is also stored incase a consumer goes offline or wants to catch up at some point.

Flume was written with Hadoop specifically in mind. It is similar to Kafka, except that data are deleted once collected and not stored.

Spark

Spark is super cool. It was built with Hadoop in mind, and is a potential replacement for MapReduce, though it can also use non-Hadoop clusters. It can do all sorts of nifty stuff with that data like machine learning on the entire cluster, analysis on streaming data in real time, and graphing.

Spark is written in Scala, so that’s the preferred language, but Python and Java are also (slower) options. Like Tez, Spark is much faster than MapReduce because it uses DAGs for optimization.

The main concept in Spark is that of a Resilient Distributed Dataset (RDD). It is an immutable, partitioned collection of records that is fault-tolerant and can be operated on in parallel. RDDs can be created by parallelizing an existing data collection, or by reading data from an external file system like HDFS. An important note is that RDDs do not have a schema, which means they have no columns. Spark DataFrames are like RDDs but with a schema. The last data structure is DataSets, which are like DataFrames but are strongly-typed (the type is specified upon creation), so they aren’t used in PySpark as Python is a dynamically-typed language.

There are two things that can be done to data objects in Spark: Transformations and Actions.

Transformations create new RDDs (because RDDs are immutable) based on some function. Since Spark uses lazy evaluation, compilers don’t actually build new RDDs as they come across each transformation, but “rather construct a chain of hypothetical RDDs that would result from those Transformations which will only be evaluated once an Action is called. This chain of hypothetical, or “child”, RDDs, all connected logically back to the original “parent” RDD, is what a lineage graph is” source.

Actions are RDD operations that do not produce RDDs as output. This could be finding a count of the data, a particular element, the mean, etc. Actions cue the compiler to start moving down the lineage graph to return the value specified by all the Transformations > Actions.

This is just barely touching the surface even of the general principles - I’ll be back to learn more about Spark for sure.

Zeppelin

Zeppelin is a notebook interface to Big Data that can interactively run scripts. It has tight integration with Spark, and can also include markdown, SQL, shell commands, etc. The built-in visualization tools are also a nice touch.

Building an Ecosystem

Work backwards from the end user’s needs:

- What sort of access patterns are anticipated? Will this be analytical queries, or huge umbers of small transactions for specific rows of data? Both?

- What availability is needed?

- What consistency is needed?

Think about requirements:

- How big is this Big Data? Is a cluster really necessary?

- How much internal infrastructure and expertise is available? Do systems that are already known in the organization fit the bill?

- Should data be retained for auditing, or purged often for privacy?

- What about security?

- What can be repurposed from existing technology, and what is the least amount of infrastructure that can be built to achieve the goal?